An Overview of Gravitational Waves

Electromagnetic Waves vs. Gravitational Waves

Down the history lane...

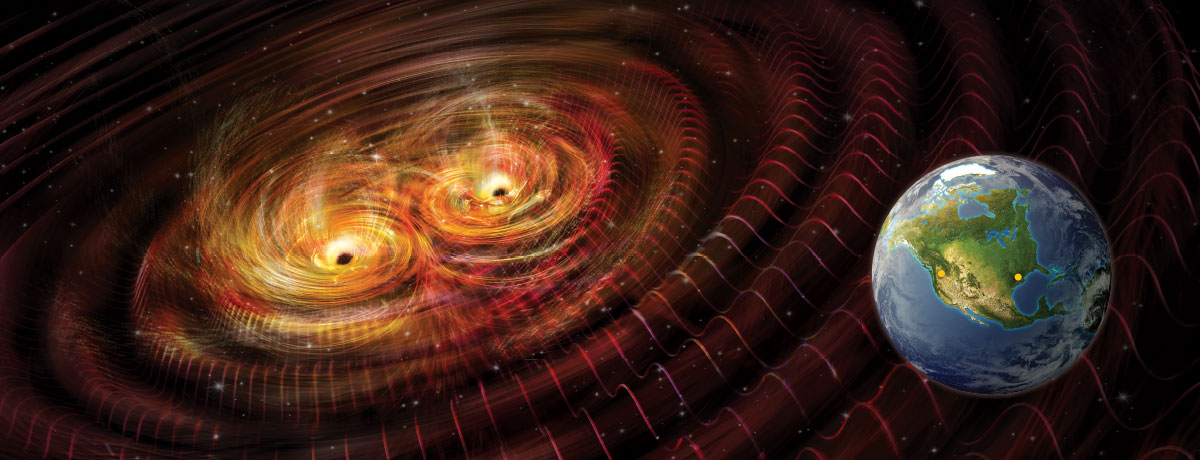

In 1609, Galileo Galilei pointed his telescope up to the night sky and made spectacular discoveries that revolutionized modern astronomy. That is the beginning of modern electromagnetic-wave (EM) astronomy. At last, humankind was no longer "blind" to the cosmos.406 years later, on September 14, 2015, the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors made the first direct detection of gravitational waves, GW150914, coming from the merger of two black holes. This event marked the beginning of gravitational-wave (GW) astronomy. At last, humankind was no longer "deaf" to the cosmos.

Merely 2 years later, on August 17, 2017, the LIGO and Virgo collaboration made the first detection of GWs from two colliding neutrons stars, GW170817. Subsequently, this same event was observed in EM waves across the whole EM spectrum in the following seconds to tens of days by EM telescopes around the globe. A new era of astronomy, multi-messenger astronomy, began on that day when joint GW-EM observations were made from the same cosmic event for the first time in human history.

The Nobel Prize in Physics in 2017 was awarded to Rainer Weiss, Kip S. Thorne and Barry C. Barish “for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves”.

What are gravitational waves?

In one sentence, gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime curvature created by accelerating masses, predicted back in 1916 by Einstein's General Theory of Relativity (GR). Let's elaborate on this. Static gravitational fields, or resting masses, are described as curvature in spacetime in GR. This is "gravity". Changing gravitational fields, or accelerating masses, generate ripples of spacetime curvature. This is "gravitational waves". As such, GWs are messengers of changing gravitational fields.As GWs pass by objects, an observer on earth would detect that distances between objects increase and decrease periodically, known as the effects of strain. GWs are extremely weak, with typical strain on the order of ~10-21, corresponding to ~10-18m length change in Advanced LIGO detectors' 4km interferometer arms. This is ~1000 times smaller than the proton radius of ~1fm, or ~10-15m.

Let's compare EM waves from Maxwell's equations with GWs from Einstein's equations:

- GWs travel at the speed of GWs (duh!), which equals the maximum speed allowed by GR, the speed of light. Thus, gravitons have zero mass. EM waves travel at the speed of light. Photons also have zero mass.

- GWs are transverse to the direction of propagation and have two tensor polarization states, "plus" and "cross". Thus, gravitons are spin-2 particles. EM waves are also transverse to the direction of propagation and have two vector polarizarion states, "x" and "y". Thus, photons are spin-1 particles.

- GWs have standard wave properties, such as overtones and higher-order modes. So do EM waves.

- GWs can not be absorbed, scattered, or shielded. But EM waves can easily be absorbed, scattered, and shielded. Thus, GWs present a unique window to probe the least understood EM-opaque astrophysical objects and to look back further in time to the beginning of the Universe.

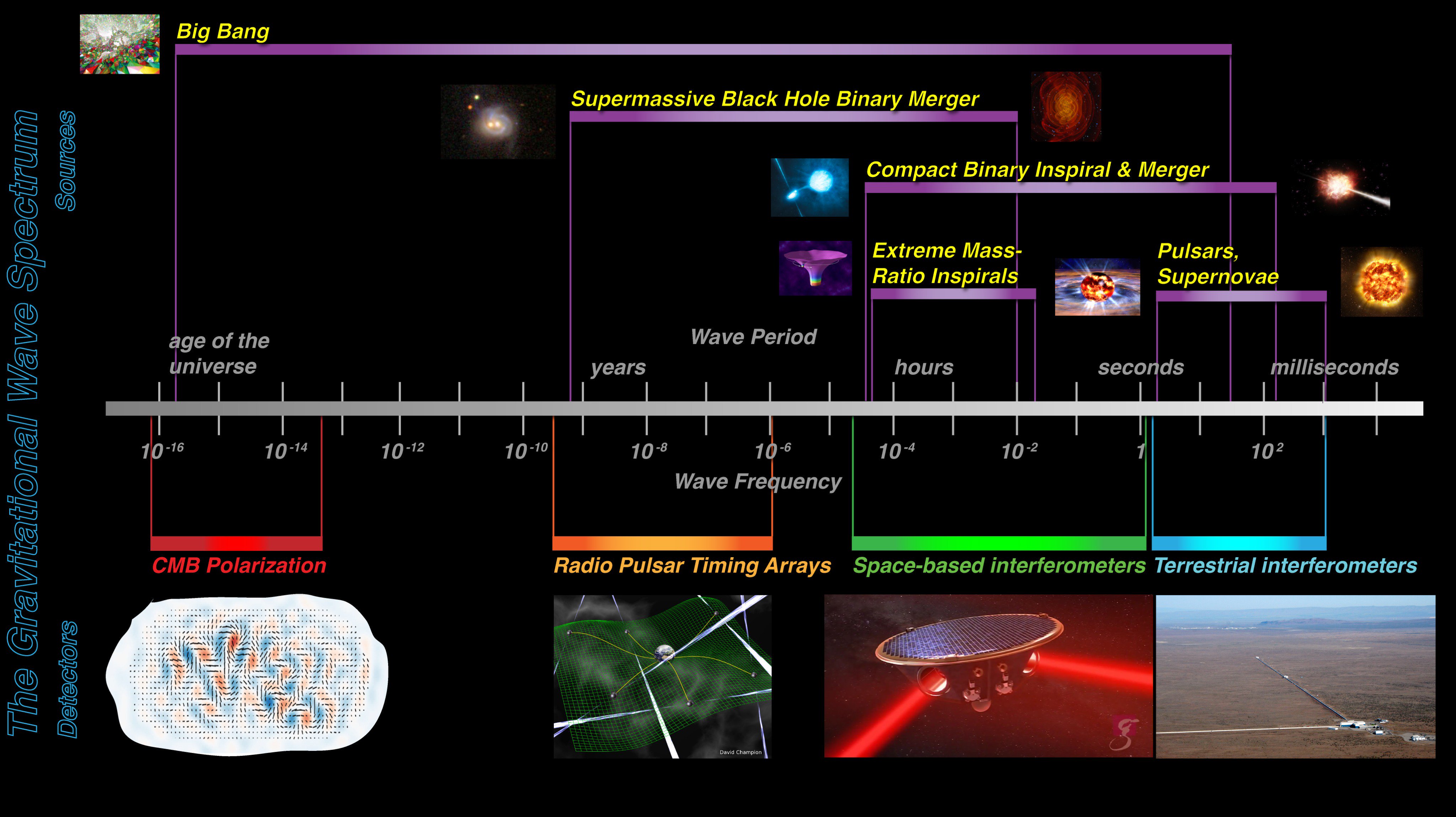

Astrophysical/Cosmological Sources of Gravitational Waves

For ground-based detectors like Advanced LIGO, there are 4 main astrophysical/cosmological sources that could produce GWs. These are coalescing compact binaries, rapidly spinning neutron stars, asymmetric core collapse supernovae, and the Big Bang. In addition to these four, we also actively search for GWs associated with gamma-ray bursts, fast radio bursts, magnetar flares, soft gamma repeaters, cosmic string cusps, etc. And of course, there might be unexpected surprises!

Compact Binary Coalescence (CBC)

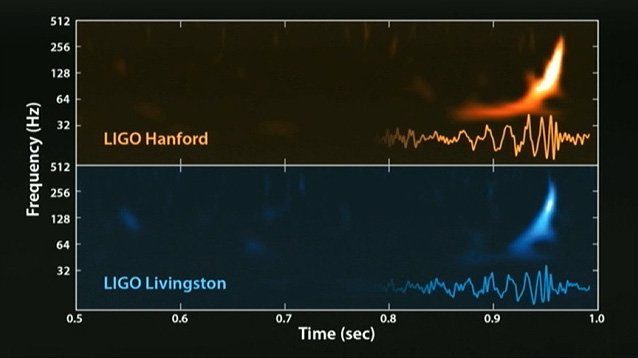

This type includes stellar systems of binary black holes (BBHs), binary neutron stars (BNSes), and neutron star - black holes (NSBHs). For LIGO, these systems produce effectively transient signals when the two bodies in a system plunge into each other and produce GW signals that fall into LIGO's sensitive frequency range. For BBHs, signals last for usually a fraction of its last second before merger. For BNSes, signals last for tens to hundreds of seconds leading up to merger. For NSBHs, signals last for anything in between. These show chirp-like signals in time-frequency plots in LIGO, which increase in both frequency and amplitude as they draw closer to merger.

CBCs have been the only detected astrophysical source up till LIGO Observing Run 3. Stellar black holes are not observable in EM waves. GWs, instead, are great messengers for their existence and a great tool to study their properties and dynamics. On the other hand, neutron stars are still very much an enigma. Just like how the first LIGO BNS signal, GW170817, enabled us to learn so much about neutron stars, GWs will continue guiding us to solve the mystery of neutron stars.

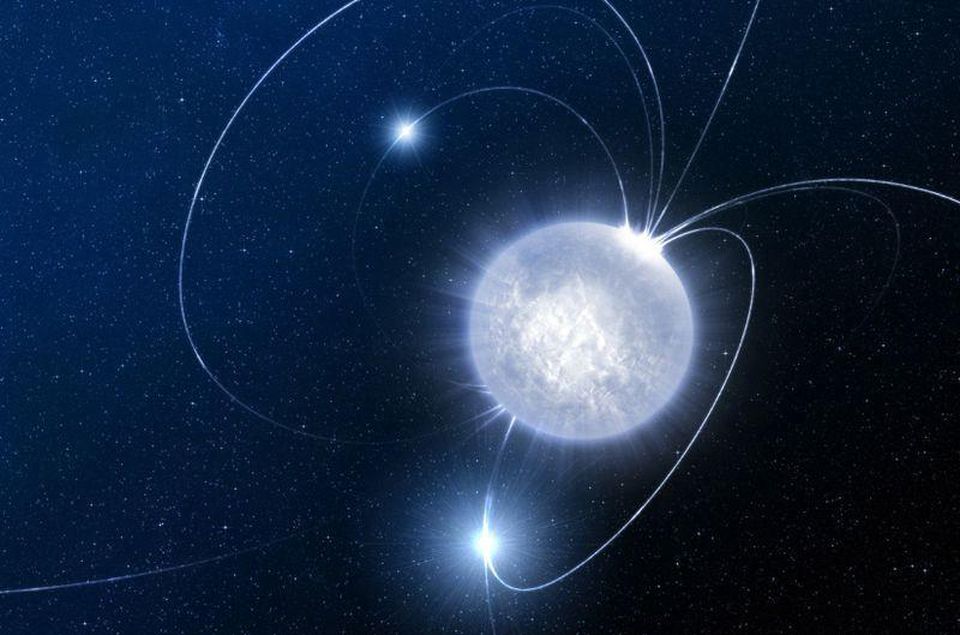

Spinning Neutron Stars

Pulsars, or spinning neutron stars, are so very dense. (In fact, their high densities are one reason we don't know much about them, as we cannot reproduce such dense environments in labs on Earth.) Added with the fact that they are rapidly spinning, pulsars are mostly spherically symmetric. Perfectly symmetric pulsars don't emit GWs. But in the case where there exist tiny deformations on a pulsar (a few centimeters of a bump is all it takes!), it will no longer be spinning spherically symmetrically. Pulsars will then emit GWs that we describe as continuous waves. Continuous waves are of fairly constant amplitudes and frequencies and are comparably weaker than other types.

Asymmetric Core Collapse Supernovae

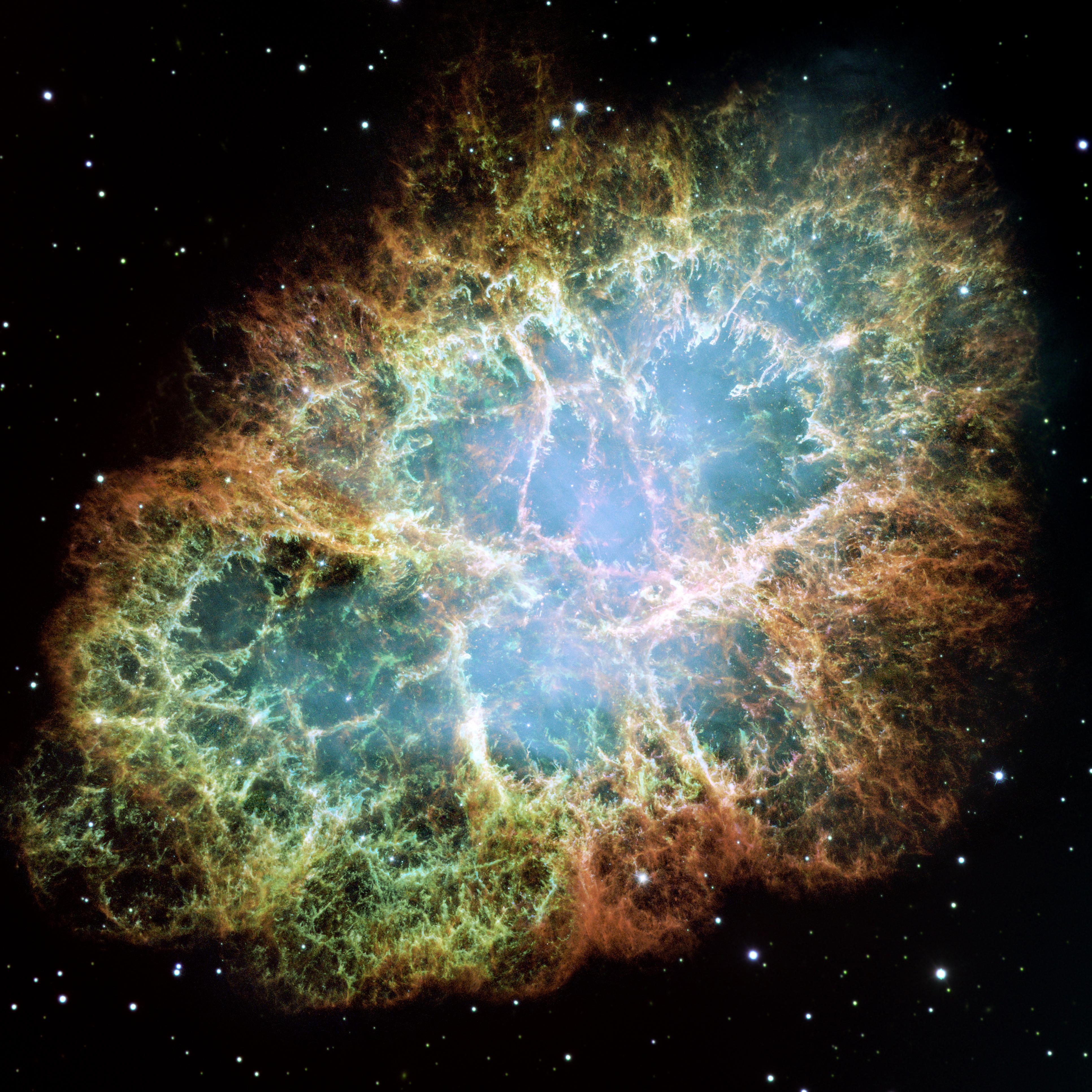

Unless there is a complete spherical symmetry in the explosion of a supernova, it will generate GWs. Such GWs are not well modeled, as supernovae are not well understood. Asymmetric core collapse supernovae could leave burst-like signals in the LIGO frequency band.

The Big Bang

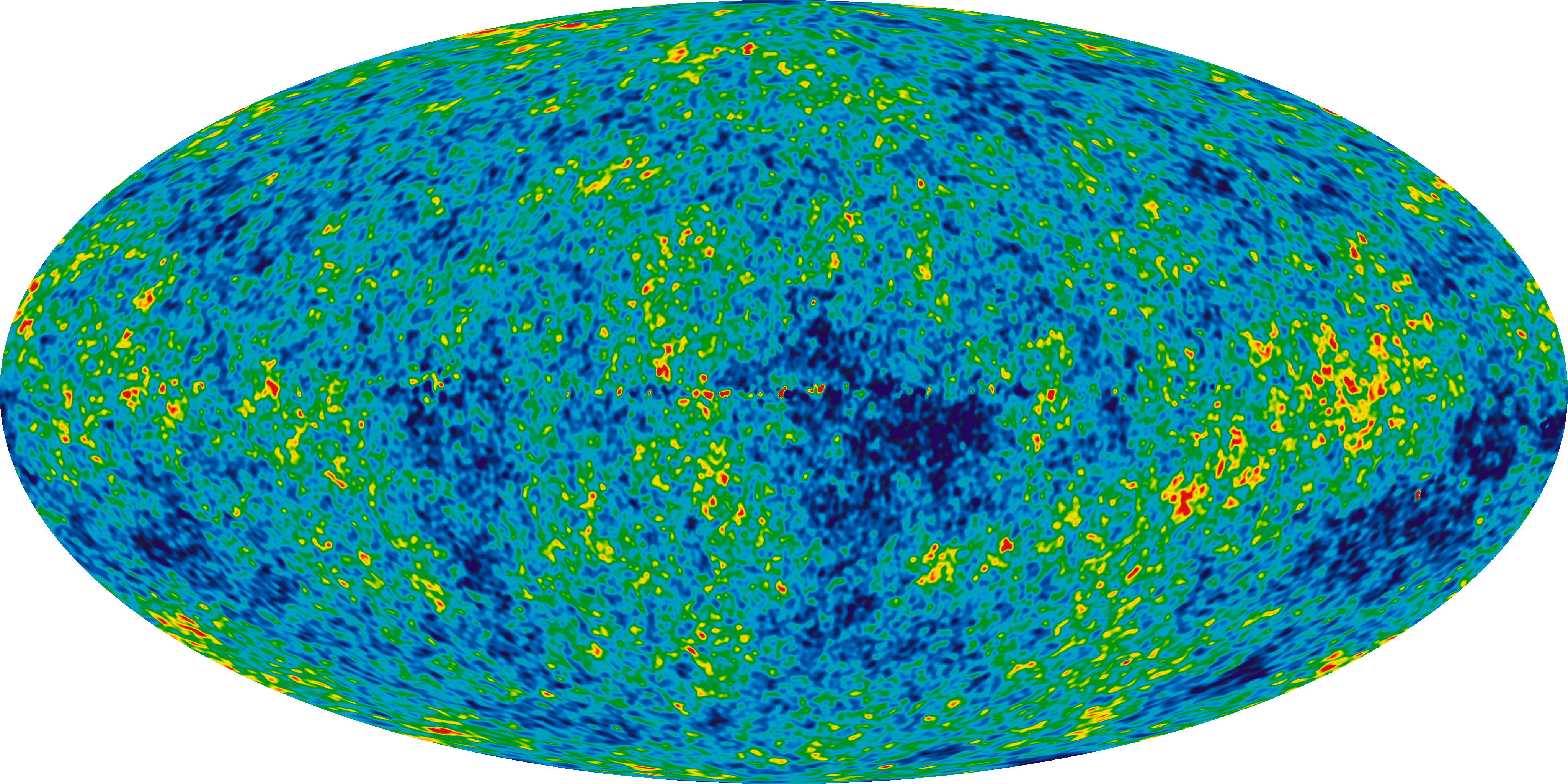

Many cosmology models suggest that the Universe went through an inflation epoch not long after the Big Bang. Inflation is a period of exponential expansion of the early Universe. If this expansion was not symmetric homogeneously, a cosmic Gravitational Wave Background (GWB) was likely created. Just like detecting the EM relic radiation from the early Universe, the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), detecting a cosmic GWB can help us learn about the origin and the early history of the Universe. GWs cannot be absorbed, scattered, or shielded. The cosmic GWB could potentially take us back to ~10-36s after the Big Bang, compared to 380,000 years after the Big Bang as learned from the CMB. Just like the CMB, the cosmic GWB is expected to be homogeneous and isotropic, which constitute stochastic GWs.

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory

LIGO Detectors

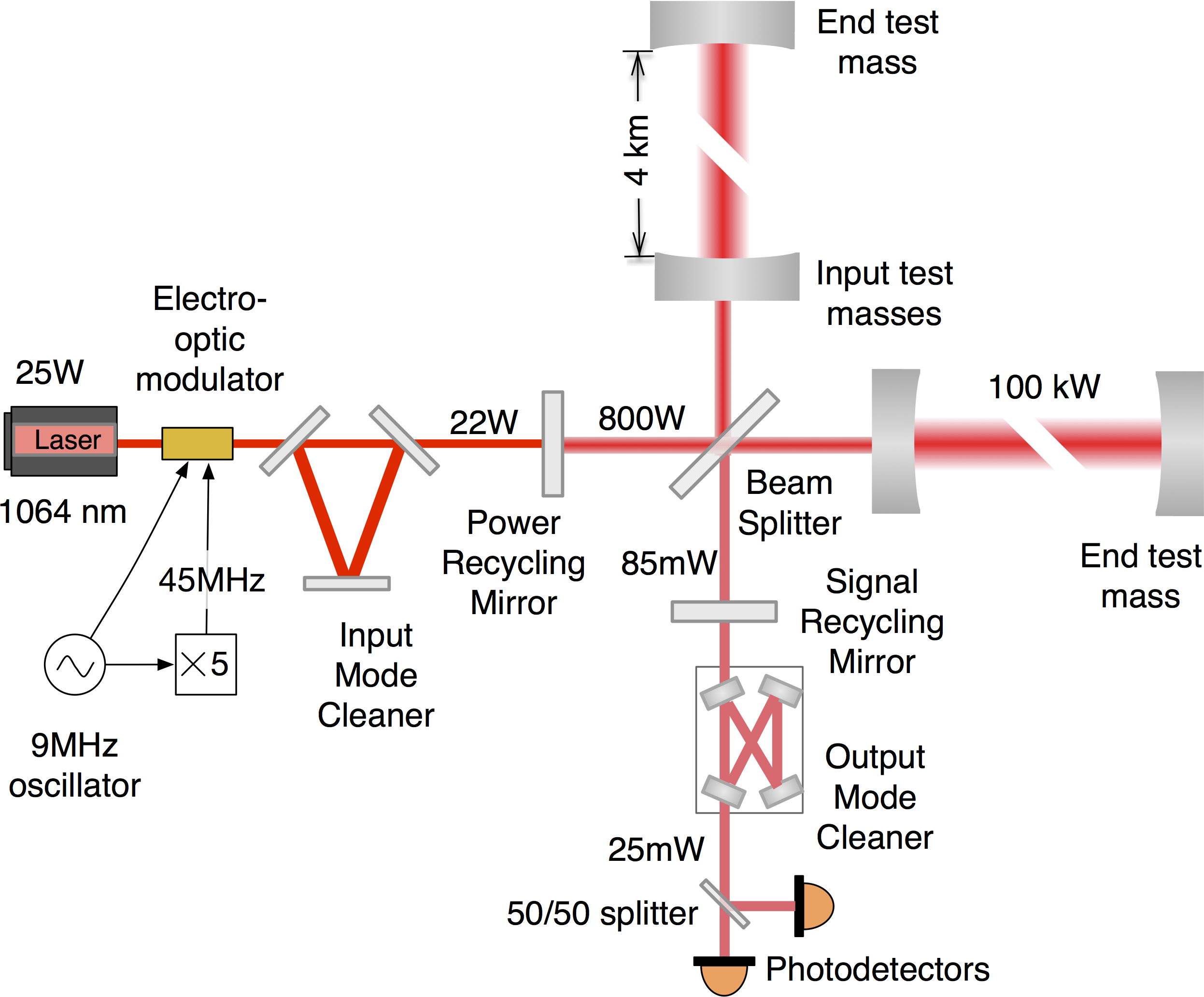

The LIGO detectors are L-shaped Michelson interferometers, consisting of two perpendicular arms, each 4km long. A passing GW stretches one arm and squeezes the other arm alternatingly. We then measure the interference pattern using photo-detectors at the readout port of each arm. Most other systems in the LIGO detectors are designed either to amplify this minute length change or to mitigate noises that might fake or mask GWs.

We need multiple detectors to confidently detect and locate GW sources. In the United States, there are two such interferometers. One in Hanford, Washington, and the other in Livingston, Louisiana. (Their locations are chosen to be remote areas with fewer human activities.) These two detectors are ~3000km apart, which induces a ~10ms detection delay. If a candidate is observed in one detector, but is not observed in the other within the light travel time between these two, the candidate is discarded.

GW Detector Network

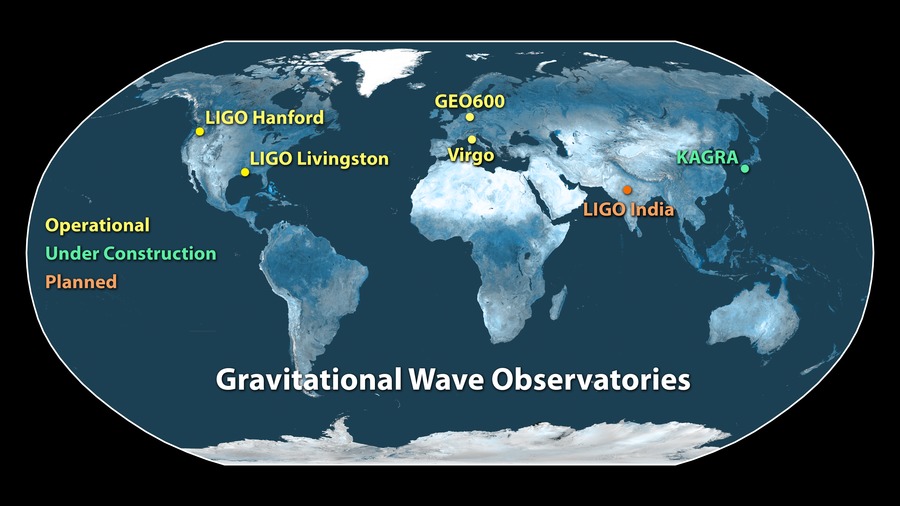

Interferometers are like antennas, sensitive to large portions of the sky and bad in localization. A global network of GW interferometers is needed for accurate sky localization of GW sources. Currently, active GW interferomters include Advanced LIGO Hanford, Advanced LIGO Livingston, Advanced Virgo in Italy, and KAGRA in Japan (recently went into commissioning in October 2019). A fifth detector, LIGO-India, is in the planning phase.

LIGO Sciences

Fundamental Physics

With GWs observed using prescribed gravitational waveforms computed through numerical relativity, once again, we have proved that "Einstein was right". BUT only for the moment being!

We are testing properties of detected GWs and looking for deviations from the predictions of GR, including the speed of GWs, Lorentz and parity violations, and more polarization states than just the tensor polarization.

GWs provide unique highly-dynamical and strong-field tests of GR. We are searching for deviations of detected signals from numerical relativity calculations, which could point us to alternative theories of gravity.

Astrophysics

From detected GWs, we can extract physical parameters of exotic stellar objects and cataclysmic events such as neutron stars, black holes and supernovae. For compact binaries, masses, spins, and eccentricities can inform us about the binary formation channels. For neutron stars, tidal deformation and other parameters like spins encode the key to dense nuclear equation of state. For supernovae, GW observations contribute directly to understanding the core-collapse supernova mechanism.

We can also learn about the underlying populations of sources from many detected individual events. For example, binary masses, spins, eccentricities, orientations, etc. We can also infer the astrophysical rates of these events.

Cosmology

We can make cosmological measurements, such as the Hubble constant, using detected GWs.

A GW source is a "standard siren" of known loudness, meaning that we can obtain a measurement of the luminosity distance to a source. If combined with a redshift measurement, either from an observation of an EM counterpart, or from statistical calculations by overlaying galaxy catalogs onto the source localization, we can probe the expansion history of the Universe.